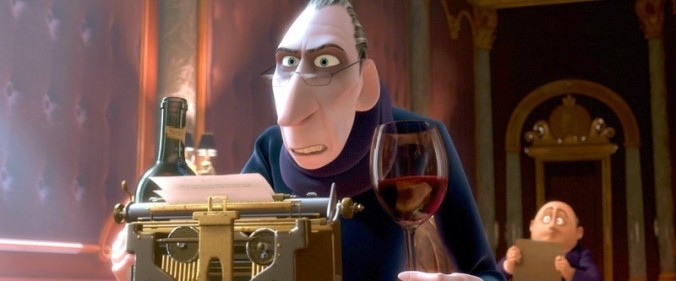

In the denouement of one of my favourite films, Ratatouille, restaurant food critic, Anton Ego poignantly states:

“Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.” Anton Ego

Given the right conditions, if someone has it in them, they can thrive to achieve great things. If that same person (or rat) finds themselves in a not-so-nourishing environment, no matter what their talent, malheureusement, they will not flourish.

So, this deep Pixar philosophy flared up inside me when when I was reading the fascinating blog exchanges between Heather Fearne and Katharine Birbalsingh on their grammar school stances. Two of the themes that emerged in this pleasant online dialogue were: that of optimising the limiting resource that is the ‘best staff’, and the purpose of schools.

Their blogs got me thinking about my own positions on grammar schools and on mixed ability teaching. But it also got me thinking about what I think the purpose of education is, and I fall firmly in Katharine’s camp on this one. For me social mobility is one of the main goals of education and the reason I am a teacher. To clarify, I absolutely believe knowledge is worth having for its own merits. Knowing things is wonderful, and the more one knows about the world, I really do believe the more enriched one’s life becomes. So ensuring pupils go through school learning about the wonders of our world and beyond, is the main goal of education for sure. But in my opinion, schools must also be actively attempting to improve social mobility and do so in an explicit, conscious and strategic way. Here is my perspective on why…

Let me begin by clarifying what I mean by social mobility (because, as I go on to explain, not everyone agrees…). Pupils enter school from various socio-economic backgrounds, cultures and with various starting points in terms of knowledge, developed skills and reading ages etc. All of these factors (and more) affect a pupil’s chances at having a choice. For me, the role of schools with respect to social mobility is to ensure that they do everything they can within their means to make sure that pupils have had the opportunities presented, knowledge acquired and skills developed to be able to make any choice they wish when they leave school. Whether that choice is going to university, doing an apprenticeship, taking a gap year, going into work, doing online courses…. whatever the pupil wishes to pursue. But the school should ensure that the opportunities, knowledge and skills are on offer that would allow any pupil in that school to capitalise on and make any destination accessible.

If a school’s curriculum and ethos is not rigorous enough for any pupil to have the opportunity to work hard, and make sufficient progress to make an application to Oxbridge*, then that school is failing its pupils. This should not be confused with meaning that every child should apply to Oxbridge. Rather, every child who might have been capable of it, whether we recognise that pupils as a potential ‘Oxbridge’ child in Year 7 or not, should have the option of applying. The litmus test to for me is this: imagine a pupils arrives in Year 7 – Chloe – and her reading age is four years behind her chronological age, she is ‘badly behaved’ – disruptive, even, and doesn’t intend to study beyond school. Is your school teaching Chloe the self-discipline she needs to develop good habits as a hard-working pupil? (Is your school teaching self-discipline at all?) Is Chloe being challenged sufficiently in her lessons so that she is making good progress? Is Chloe going to catch up with her reading? Will Chloe think it is a possibility for her to go to university? Will she have the knowledge of all the options available to her for when she leaves school? My point is this – you never know who is capable of achieving remarkable things based on their prior attainment/behaviour/SEN label. What right do I have to decide a pupil is not Oxbridge material without first offering them the very best curriculum, inculcating the very best habits and offering the knowledge to access such institutions? If schools get things right, pupils can and will turn around. I’ve seen remarkable transformations. That is social mobility.

Even if after all of this, Chloe doesn’t choose to apply to Cambridge or doesn’t get the grades to do so, we can more validly claim this was down to her rather than a failing of the school. Maybe Chloe didn’t work hard enough, or maybe she took longer to learn the content and so by the time she sat her exams, despite working hard, she didn’t make the required grades. Of course, schools must always ask themselves what more could they have done. I am not asserting that schools that do not send lots of pupils to Oxbridge are failures – I am simply saying that schools should be asking themselves if they are optimising the use of their resources well enough to make the only limiting factor for a pupil’s achievement their own hard work or ‘ability’. We as teachers in the state sector have the responsibility of using our capital optimally give every pupil that enrols to our school the best chance to access any part of society that they would have been able to if they went to Eton or Harrow.

In the aforementioned blog exchanges, Heather talks of one of the short-comings of comprehensive schools when compared to successful grammars: the ‘critical mass of staff and pupils who revel in intellectual pursuits’. Achieving this critical mass in all comprehensives is unrealistic, idealistic. This is what tips some in favour of grammar schools: it is better to give the brightest pupils the intellectual environment than to spread those pupils and the teachers they attract so thin that the brightest are not stretched. Conversely, others may disagree with grammars on the grounds that draining other pupils of these ‘keenies’ – teachers and pupils – will lower their achievement.

I agree with both authors that comprehensive schools need improving to provide this stimulating culture. It needs to become pervasive. Although Heather says that achieving the critical mass of such teachers is idealistic, I think it is possible with some considerable systematic change (difficult, I know, but possible). For this to happen I think the following needs to happen:

- The idea of social mobility I have laid out above must be the thinking across schools – if teachers don’t believe it, they won’t reach for it and pupils will miss out.

- Teacher training must make creating an academic ethos in schools an explicit component.

- We must reject the progressive pedagogy that does detract from transmitting rigorous academic knowledge to ensure pupils do have access to the ‘best of what has been thought and said’.

- We must continue improving recruitment and retention of highly qualified teachers and raise the status of the profession.

There are already barriers. My first point, on social mobility, is not widely accepted. In her blog, Sue Cowley wrote about some of her confusions regarding the very concept of social mobility, making statements such as,

‘Not all of us want to climb the tree, even for all the money in the kingdom.’

I see her point, but I think she underplays the very thing that defines social mobility for me: choice. Sue goes on to say,

‘I’m not completely clear whether we have to earn our way to the top through hard work, or whether we only get there through intelligence, or perhaps if some people believe that hard work is all that stands between most of the population and being the Prime Minister. For anyone with any kind of learning disability, the idea that ‘all it takes is hard work’ and that they have to ‘earn their way’ out of poverty is downright insulting.’

I think this again is where mine and Sue’s interpretation of what social mobility is differs. It’s not that everyone is capable (or indeed wants) to become Prime Minister, but that a Prime Minister should be able to come from anywhere, and schools shouldn’t have any limits that hinder that goal for an individual pupil who could have become PM.

The Ratatouille plot is quite poignant: it’s so important to believe that ‘anyone can cook’, and that will mean schools do everything they can to allow a ‘great chef to come from anywhere.’ If not, then social mobility is not an explicit part of teachers’ thinking, and consequently teachers will miss asking the critical questions I posed earlier. No, schools shouldn’t take on every problem and barrier that society throws for our pupils, but we should be asking: are schools doing enough?

*Oxbridge is used as an example of excellence since it has some of the most demanding admission offers globally. Reaching and thriving there requires a fair amount of cultural capital.

Thanks for the mention. For me, it is the assumption that everyone might want to become PM, or even that everyone might want to go to Oxbridge, that one of my sticking points. Who are we to say that this is at the top of the tree? Is it just how much you earn, or how much power you have, that makes a life worth living? What happens in a society where everyone is focused on this end? Do we end up undervaluing all the crucial careers that go to make up a society, such as social care or nursing or aid work? And what about the child with a learning disability – are they somehow ‘less’ because they are not in the position to make that ‘choice’? Are some children from disadvantaged homes less ‘deserving’ than others, because (we feel) they work less hard? And who exactly is going to move down to let others move up? I believe these are serious questions that need answering if you truly believe in the concept of ‘social mobility’, because essentially you are talking about a meritocracy in which all children have to compete but only some can ‘win’, and in which what you might actually ‘win’ is very ill defined. (It’s also worth considering why it might be that we have made little or no progress in social mobility up to now, despite the millions being pumped into it, but that’s a whole other question.)

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment!

For me, it is not that we are defining a ‘top aspiration’, but rather, ensuring that our schools provide sufficient rigour for any of these to become realistic *choices*.

A child with a learning disability is no less than a child without a learning disability. My social mobility argument would ask: does that child with learning disability have every choice open to them too? Is the school working for that child to access as many opportunities as they can?

My take on this at the moment, is that most schools can make gains in this area by being pro-active in creating a more academic culture in their schools, by accepting that a broad knowledge-base is worth having, and that discipline is essential for this.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

I agree with Sue’s points on self actualisation. I also totally agree that all students should have access to a rigorous academic education. My concern would be to focus on Oxbridge does cause problems. At my sixth form this was heavily promoted and revered and a whole host of students who have gone on to do equally valuable things with their lives felt less valued at that time. That is unacceptable. Also, there are not finite resources and they become unevenly distributed once a society becomes fixated on one pinnacle of success, such as Oxbridge. I will be proud of each of my students when the knowledge and skills they have worked hard to gain serve them well in a plethora of ways. As well as giving everyone access to good quality academic education we also need to give more recognition and gratitude to the best that everyone achieves. We need chefs, waiters, maintenance workers, careers, engineers who did or did not go to Oxford and great parents as well as film stars, MPs, doctors, entrepreneurs, IT security experts and inventors. We also need a society that does more to support lifelong learning and adult education. I understand that you appreciate all of this; however; to my mind as soon as someone focuses of Oxbridge it seems like an over-simplification and places the focus of success on centres of white male priveledge. Yes, that needs to be challenged by widening the intake; however, the concept of what constitutes ultimate achievement needs to be challenged too. For many individuals their midwives and careers can become the most important people in their lives. Yet they are underpaid and undervalued. The narrative of what constitutes success needs changing in parallel with the quality of academic education available.

LikeLike